“There is such a strong feeling in India over the invasion by China..."

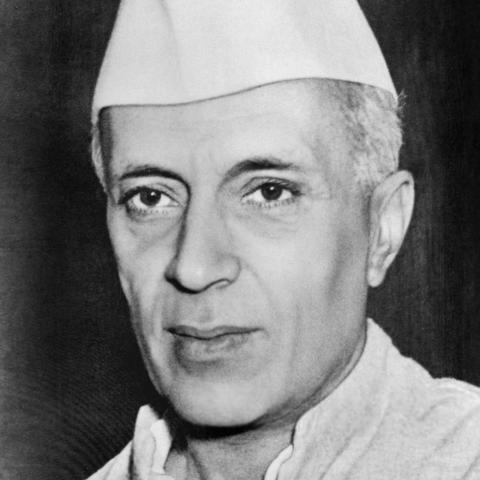

Jawaharlal Nehru to Bertrand Russell

December 4, 1962

In September 1962 skirmishes broke out between India and China along their disputed border in the Himalayas. On October 20, China initiated an offensive and overran the area, forcing the Indian army to retreat. Thousands of miles away, at his home in Wales, Bertrand Russell was keeping a close eye on the situation, just as he was doing with the simultaneous occurrence of the Cuban missile crisis (see telegram from John F. Kennedy). Russell’s intervention in such international affairs had increased his workload to such an extent that he and his followers had decided to establish a Foundation to support their efforts. In fact, an old acquaintance, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru (1889-1964) had just agreed to serve as a sponsor of the new Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation. Accordingly, Russell was very comfortable in cabling and writing to Nehru about his country’s dispute with China. (Russell also started a correspondence with Premier Zhou Enlai of China). When China unilaterally adopted a ceasefire on November 21, bringing about an end to the war, Russell wrote to Nehru again, urging him to accept the ceasefire and to engage in negotiations with China. Otherwise, Russell feared, the conflict between Asia’s two largest countries might trigger a nuclear war.

Russell and Nehru had by now known each other for thirty years and had been well aware of each other long before that. Nehru acknowledged Russell as one of his favourite authors as early as 1912 and, during periods of imprisonment for contesting British rule of India, found comfort in such works as Religion and Science and A Free Man’s Worship. For his part, Russell had long been a supporter of Indian self-rule and was extremely critical of the often violent suppression of the anti-colonial movement in India. From 1930 to 1938 Russell had also served as president of the India League, a British-based organization that advocated full independence for India. During this time, he had heard much about the rising star of India’s Congress party and finally met Nehru during his visit to England in 1935. The two shared many common interests and convictions. Both had studied at Trinity College, Cambridge, and even acknowledged Shelley as their favourite poet. More significantly, however, both had socialist leanings, felt that religion had no place in the governing of a nation, and, unlike Gandhi, thought that the influence of western institutions and ideas on India was often positive.

Russell had great admiration for Nehru. In his 1942 review of Nehru’s Glimpses of World History (written while Nehru was in prison), Russell had noted: “it is enough to say that, considering that it was written without access to books except those in the prison library, it shows astonishing breadth of knowledge. I do not believe that any politician in the Western world knows as much history.” When Nehru became India’s first Prime Minister after independence in 1947, Russell was pleased with the direction in which Nehru led the world’s newest and largest democracy, especially in adopting the position of a “non-aligned” foreign policy, independent of both the American-led and Russian-led Cold War blocs. In 1960, just two years before the Cuban missile crisis and the Sino-Indian war, Russell wrote: "Nehru is known to stand for sanity and peace in this critical moment of history. Perhaps it will be he who will lead us out of the dark night of fear into a happier day."

It was with some surprise to Russell, therefore, at least initially, that Nehru dug in his heels so strongly against China in 1962. In this December 4th letter, Nehru offered to Russell some of the reasons for his stand. The fact that Nehru goes to such lengths with Russell shows the high esteem in which he held the older man. He wrote: “There is such a strong feeling in India over the invasion by China that no Government can stand if it does not pay some heed to it.” He adds that “a sense of national surrender and humiliation” would result in “a very serious setback” to “all our efforts to build up the nation.” He then points out that “the popular upsurge all over India can be utilised for strengthening the unity and capacity for work of the nation.” Indeed, Nehru was facing pressures at home, including within his own Congress party. While his sympathies resided with the party’s left wing faction, much of his attention was diverted to shoring up the support of the right wing which was clamouring for action against China, as was the public majority. For the time being, Nehru felt that negotiations with China would just have to wait.

Russell understood the situation faced by Nehru. As he had observed to Nehru in a letter the previous year: “I can understand your envying me, because a private person is not obliged to bear in mind the very complex considerations which beset a head of state.” At the same time, however, Russell was dismayed by Nehru’s position. He was also disappointed by the support given to India by the United States and Britain, including the supply of arms, as he saw this as weakening India’s role as a leading non-aligned nation. Russell and his new Foundation increased their efforts to encourage a lasting peace between India and China, even sending envoys in the summer of 1963 to meet with Nehru and Zhou. While the two nations exchanged diplomatic overtures, little progress was made, and, to this day, the border issues between them remain unresolved.

Tragically, just as Nehru was starting to take a more forceful stand against the right wing in his party and to suggest that negotiations with China should actually occur, he died, in May 1964, at the age of 74, exhausted by the demands of office. His death was mourned not only in India, but around the world, and Russell was one of many who paid tribute. Writing in The Minority of One later that summer and remembering their long acquaintance, Russell observed: “I do not believe his greatness is fully appreciated, but I have every confidence that if mankind is allowed to survive, he will be recognized in a manner adequate to his stature.”

There are over twenty letters from Nehru in the Russell Archives. Several of those dealing with the Sino-Indian War have been published in Russell’s Autobiography or in Unarmed Victory, which includes Russell’s account of his intervention in that conflict. Meanwhile, the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation, which Nehru supported, continues its work today.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1944-1967 (Volume III). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1969. (2) Bertrand Russell. Unarmed Victory. Allen & Unwin, 1963. (3) Bertrand Russell, “Nehru’s Credo.” Common Sense, II (September 1942): 319-320 (Copy in Russell Archives, C42.06). (4) Bertrand Russell, ""[Praise of Nehru]." Wisdom, 34 (June 1960): 2 (copy in Russell Archives C60.16). (5)Bertrand Russell, “Jawaharlal Nehru 1889-1964: Did He Succeed?” The Minority of One, 6, no. 7 (July 1964): 12-13 (Copy in Russell Archives C64.50). (6) Letter (copy) from Bertrand Russell to Jawaharlal Nehru, 30 September 1961 (Russell Archives, Box 1.58, India, Folder 32-a). (7) Ronald W. Clark. The Life of Bertrand Russell. Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975. (8) Andrew G. Bone, “Russell and Indian Independence,” Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies. N.S. 35 (Winter 2015-16): 101-153. (9) Nicholas Griffin, ed. The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Public Years, 1914-1970. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. (10) John B. Alphonso-Karkala. Jawaharlal Nehru. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1975. (11) Tariq Ali, An Indian Dynasty: the story of the Nehru-Gandhi Family. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1985.

CONFIDENTIAL PRIME MINISTER’S HOUSE

NEW DELHI

No. 2155-PMH/62 December 4, 1962

Dear Lord Russell,

I must ask for you forgiveness for the delay in answering your letter of the 23rd November and your telegram which came subsequently. You can certainly write to me whenever you wish, and I shall always welcome your views and advice.

I have given much thought to what you have written. I need not tell you that I am much moved by your passion for peace and it finds an echo in my own heart. Certainly we do not want this frontier war with China to continue, and even more certainly we do not want it to spread and involve the nuclear powers. Also there is the danger of the military mentality spreading in India and the power of the Army increasing.

But there are limits in a democratic society to what a Government can do. There is such strong feeling in India over the invasion by China that no Government can stand if it does not pay some heed to it. The Communist Party of India has been compelled by circumstances to issue a strong condemnation of China. Even so, the Communists here are in a bad way, and their organization is gradually disappearing because of popular resentment.

Apart from this, there are various other important considerations which have to be borne in mind in coming to a decision. If there is a sense of national surrender and humiliation, this will have a very bad effect on the people of India and all our efforts to build up the nation will suffer a very serious setback. At present the popular upsurge all over India can be utilised for strengthening the unity and capacity for work of the nation, apart from the military aspect. There are obvious dangers about militarism and extreme forms of nationalism developing, but there are also possibilities of the people of our country thinking in a more constructive way and profiting by the dangers that threaten us.

If we go wholly against the popular sentiment, which to a large extent I share, then the result will be just what you fear. Others will take charge and drive the country towards disaster.

The Earl Russell,

Plas Penrhyn, Penrhyndeudraeth, Contd…

Merioneth, England.

-2-

The Chinese proposals, as they are, mean their gaining a dominating position, specially in Ladakh, which they can utilise in future for a further attack on India.[1] The present day China, as you know, is probably the only country which is not afraid even of a nuclear war. Mao Tse-tung[2] has said repeatedly that he does not mind losing a few hundred million people as still several hundred millions will survive in China. If they are to profit by this invasion, this will lead them to further attempts of the same kind. That will put an end to all talks of peace and will surely bring about a world nuclear war. I feel, therefore, that in order to avoid this catastrophe and, at the same time, strengthen our own people, quite apart from arms, etc., we must not surrender or submit to what we consider evil. That is a lesson I learned from Gandhiji.[3]

We have, however, not rejected the Chinese proposal, but have ourselves suggested an alternative which is honourable for both parties. I still have hopes that China will agree to this. In any event, we are not going to break the cease-fire and indulge in a military offensive.

If these preliminaries are satisfactorily settled, we are prepared to adopt any peaceful methods for the settlement of the frontier problems. These might even include a reference to arbitration.

So far as we are concerned, we hope to adhere to the policy of non-alignment although I confess that taking military help from other countries does somewhat affect it. But in the circumstances we have no choice.

I can assure you that the wider issues that you have mentioned are before us all the time. We do not want to do something which will endanger our planet. I do think, however, that there will be a greater danger of that kind if we surrender to the Chinese and they feel that the policy they have pursued brings them rich dividends.

Yours sincerely,

Jawaharlal Nehru

[1] While the Sino-Indian War lasted only for 33 days, from 20 October to 21 November 1962, the diplomatic back and forth would drag on for months and would never really be settled.

[2] Mao Tse-tung, or Mao Zedong (1893-1976), was Chairman of the Communist Party of China and ruled the country from 1949 to his death in 1976.

[3] Mohandas Karamchand ‘Mahatma’ Gandhi (1869-1948), was leader of the Indian independence movement and revered proponent and practitioner of peaceful civil disobedience.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 1.58, India, File 32b. Public domain in Canada. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, the user assumes all risk.