“we are not yet … at the point where it is not possible to speak and advocate openly in this country”

Arthur Miller to Bertrand Russell

November 2, 1966

In his Autobiography, Russell recounted the beginning of his concern about the Vietnam War: “Since shortly before April, 1963, more and more of my time and thought has been absorbed by the war being waged in Vietnam.” Russell was one of the earliest opponents of the war, but his initial anti-war efforts were largely ignored in the West. The numerous letters and articles he sent to major American and British newspapers and other publications, condemning the American involvement in the war, frequently went unpublished. In 1965, when the United States initiated the bombing of North Vietnam, Russell dispatched letters and cables to American President Lyndon B. Johnson, but they were never answered (unlike his correspondence with Vietnamese President Ho Chi Minh, which was friendly and long-lasting; from Ho’s perspective, of course, it was of great benefit to have the support of such a prominent western intellectual).

The situation began to change in 1966. First, Russell’s Peace Foundation was instrumental in establishing the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign, which would go on to organize mass protests and other anti-war activities which drew wide attention. Perhaps more significantly, the Foundation gained a presence at the trial of one David Mitchell, an American conscientious objector who refused to be drafted on the grounds that the United States was committing war crimes in Vietnam. An American lawyer with ties to the Foundation agreed to defend Mitchell, and the Foundation sent Russell’s secretary, Ralph Schoenman, to Vietnam to gather evidence of war crimes. While Mitchell was, not surprisingly, convicted, Schoenman was able to present his findings to the media. As Russell commented: “Schoenman’s reports were of extreme importance since they contain not only first-hand observation but verbatim accounts given by victims of the war attested to both by the victims themselves and by the reliable witnesses present at the time the accounts were given.”

The experience also solidified for Russell and Schoenman an idea that had been presented to them a few months earlier by Minority of One editor M.S. Arnoni, namely, the establishment of a war crimes tribunal to bring American atrocities in Vietnam to the public eye. Efforts gained traction throughout 1966, and the Foundation took the lead in recruiting tribunal members with a plan to have them meet later in the year to establish their own operating procedures. Russell recounted: “In the summer of 1966, after extensive study and planning, I wrote to a number of people around the world, inviting them to join an International War Crimes Tribunal.”

Russell was criticized for seeking to recruit only those who were known to be critical of the American role in Vietnam, but he defended himself in his 1967 book, War Crimes in Vietnam: “I do not maintain that those who have been invited to serve as members of the Tribunal are without opinions about the war. On the contrary, it is precisely because of their passionate conviction that terrible crimes have been occurring that they feel the moral obligation to form themselves into a Tribunal of conscience, for the purpose of assessing exhaustively and definitively the actions of the United States in Vietnam. I have not confused an open mind with an empty one.” Meanwhile, in his Autobiography, Russell revealed that he had extended an invitation to President Johnson to appear at the Tribunal, but, as Russell quipped: “he was too busy planning the bombardment of the Vietnamese to reply.”

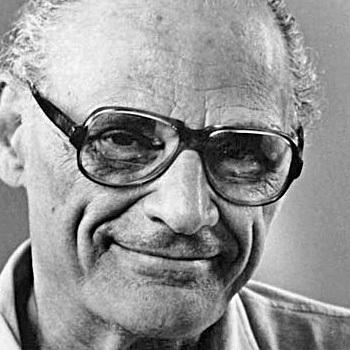

One of those who did reply was the award-winning American playwright, Arthur Miller (1915-2005), author of such classics as All My Sons, Death of a Salesman, and The Crucible. Miller was an obvious choice as he was an outspoken critic of the war and a frequent speaker at anti-war demonstrations. He was also an admirer of Russell and, along with many others, had paid tribute to Russell on the occasion of his 90th birthday in 1962, writing: “Bertrand Russell has done much in his life, but above all he has fused a vivid sense of life with truly free intelligence; for this invention, especially in this purblind time, we are all in his great debt.”

Much to Russell’s disappointment, Miller declined the invitation to join the Tribunal, for reasons expressed in the letter displayed here. Calling attention to the make-up of the Tribunal, he astutely told Russell that “the net of the effort might easily be washed out as simply one more ‘propaganda’ effort against the Johnson administration.” He continues: “my own role as an opponent of this horrible war is more effective … if it remains an appeal primarily to Americans.” He concludes: “we are not yet, and I pray we will never be, at the point where it is not possible to speak and advocate openly in this country. I feel that so long as this is the case I ought not send my criticism from outside.”

This is the only exchange of letters between Russell and Miller in the Russell Archives. Meanwhile, as we can see in the next letter in this series, from James Baldwin, the Foundation was successful in recruiting several prominent individuals to serve on the Tribunal, which held sessions in Stockholm and Copenhagen in 1967.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1944-1967 (Volume III). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1969. (2) Bertrand Russell. War Crimes in Vietnam. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1967. (3) Nicholas Griffin, ed. The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Public Years, 1914-1970. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. (4) Stefan Andersson, “A Secondary Bibliography of the International War Crimes Tribunal: London, Stockholm and Roskilde.” Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies, n.s. 31 (Winter 2011-12): 167-187. (5) Martin Gottfried, Arthur Miller: his life and work. Perseus Books Group, 2003. (6) Into the 10th decade: tribute to Bertrand Russell. 1962

ARTHUR MILLER

November 2nd, 1966

Mr. Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation

3 & 4 Shavers Place

London SW 1

Dear Mr. Russell;

Your letter and telegram[1] only reached me the other day, having been addressed to a defunct agency which used to represent me some years ago.

It would be impossible for me to leave the country at any time in the near future, due to professional and personal affairs, responsibilities impossible to shake off.

I had read in the press of the forthcoming Tribunal,[2] and as an opponent of U.S. participation in the Viet Nam war, I am deeply interested in any attempt to stop the fighting or mitigate the suffering it causes. I must confess, at this juncture anyway, that I had and still have some fear that if such a tribunal cannot enlist some typical pro-war advocacy, and if at the same time an ultimate judgement is not participated in by a personality or personalities who have a claim to non-partisanship, the net of the effort might easily be washed out as simply one more “propaganda” effort against the Johnson administration.[3] As you know, the differential in power between the United States and the rest of the world is such, that world opinion, however important in the long run, is not the critical factor at this moment as compared with the sentiment inside this country.

It is the American people who must demand the end of the fighting, and anything which can bring them the insight to know how their power is being used, as opposed to how they think it is used, is very valuable. But the tragic fact is that with their military honor committed, an accusation of war crimes will have to come from sources very difficult indeed to defame if such charges are to penetrate the apathy and despair of some, the unwillingness to face such realities of others, and to reverse the congenital human incapacity to see oneself in a role one has always condemned.

[second page]

None of which is meant to depreciate in the slightest the moral right and duty to protest what is going on by the eminent list of people mentioned in your letter. But in my judgement, my own role as an opponent of this horrible war is more effective, if it can be said to have an effect, if it remains an appeal primarily to Americans. For me to address them through an international forum levelling such charges as I imagine will ensue, would perhaps gratify those already committed against the war, but would do little to sway the others.

In addition, I say this because we are not yet, and I pray we will never be, at the point where it is not possible to speak and advocate openly in this country. I feel that so long as this is the case I ought not send my criticism from outside.

I wish to thank you for inviting me. I hope that one day I can have the pleasure of meeting you and perhaps discussing this further.

Sincerely yours,

[signature]

Arthur Miller

Trophet Road

Roxbury, Conn. 06783

U.S.A.

[1] Russell’s request that Miller join the Tribunal. A copy of the letter is in the Russell Archives, attached to this letter from Miller. A copy of the telegram is not present.

[2] The International War Crimes Tribunal

[3] President Lyndon B. Johnson

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 10.03, Document 171059. Copyright © Arthur Miller, used by permission of The Wylie Agency (UK) Limited. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, permission of the copyright holder is required.