“I am happy that you have asked me to be a member of the tribunal and I will be very honored to serve”

James Baldwin to Bertrand Russell

January 9, 1967

As we have seen in the introduction to the Arthur Miller letter, Russell and his Peace Foundation spent much of the summer of 1966 recruiting members to serve on the International War Crimes Tribunal to investigate charges of American war crimes in Vietnam. While Miller declined Russell’s invitation, several other prominent individuals from around the world accepted, including French philosopher Jean Paul Sartre, who served as executive president (Russell was honourary president); French writer Simone de Beauvoir; former Mexican president Lazaro Cardenas; Amado Hernandez, poet laureate of the Philippines; and many more.

Another who accepted Russell’s invitation was American novelist, playwright, and essayist, James Baldwin (1924-1987). By this time, Baldwin was one of the best-known writers of the civil rights movement. His first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, had been published in 1953, and his first collection of essays, Notes of a Native Son, in 1955, but he really burst onto the American scene in 1963 with an essay that was published in the New Yorker and later appeared in book form as The Fire Next Time. For this work, he was awarded the George Polk prize for journalism. On May 17, 1963, Baldwin appeared on the cover of Time magazine under the banner ‘The Negro’s Push for Equality’. He became a frequent guest on television talk shows and a regular speaker at civil rights rallies. He associated with other civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, as well as celebrities such as Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, and Lena Horne. However, Baldwin did not fall into any one civil rights camp, and his written work covered other issues as well, including the nascent gay liberation movement.

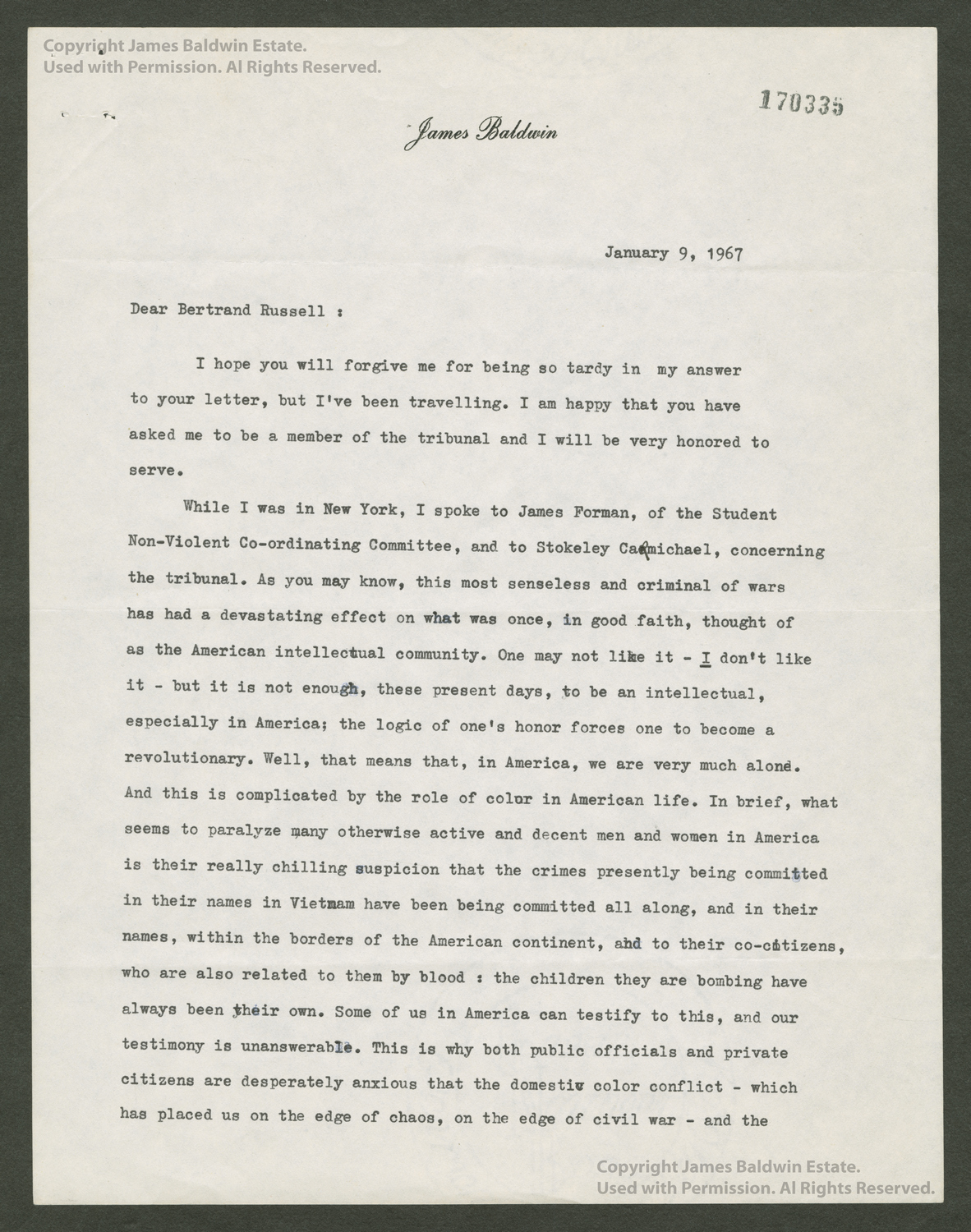

Russell and Baldwin had met in 1965 when Baldwin was visiting London, and Russell was impressed enough to write to Baldwin the following year, inviting him to join the Tribunal. In his reply, displayed here, Baldwin tells Russell: “I am happy that you have asked me to be a member of the tribunal and I will be very honored to serve.” He goes on to decry “this most senseless and criminal of wars” and laments that “it is not enough, these present days, to be an intellectual, especially in America; the logic of one’s honor forces one to become a revolutionary.” Baldwin then connects the war with “the domestic color conflict,” a connection, he says, the authorities never want drawn. He adds starkly: “Yet, the conflicts are, of course, connected, if only in the mind … of the black boy whose reward for not having been murdered at home is to be sent off to be murdered, in defense of his opressors [sic], in a strange land.”

Ironically, despite the enthusiasm shown in this letter, Baldwin ended up not attending any of the Tribunal sessions in Stockholm and Copenhagen in May and November of 1967 (though his name continued to appear in Tribunal publications). He did not explain his absence directly to Russell but, in fact, he was having second thoughts about the Tribunal, concluding that it did not adequately address what he viewed as the racist component of the war, that its leadership was too European in its perspective, and that the Tribunal as a whole was anti-American. Baldwin thought that Europeans should be holding tribunals about the crimes he charged were being committed by the white government in South Africa and the French government in Algiers. In the article “War Crimes Tribunal,” published in Freedomways in the summer of 1967, Baldwin said that any official tribunal about the Vietnam War should be held in Harlem.

While the International War Crimes Tribunal may have been diminished by Baldwin’s absence, the sessions went ahead as planned. Not surprisingly, the western media, for the most part, dismissed the Tribunal as anti-American propaganda and as having no mandate to charge anyone with war crimes, unlike the Nuremburg trials after the Second World War. In his book, War Crimes in Vietnam, Russell clarified the purpose of the Tribunal as being very different from Nuremburg: “Our tribunal … commands no State power. It rests on no victorious army. It claims no other than a moral authority.” He added: “The Tribunal members will function as a commission of inquiry, and the commissioners under its direction will prepare the evidence, subjecting documentary data to thorough and verifiable scrutiny.”

And prepare the evidence they did. In retrospect, despite moments of theatrics and strident language, the Tribunal was a remarkable achievement in that its findings were based on witness accounts and documentary evidence, including films and photographs. Much of the evidence showed the use of cluster bombs, the horrors of napalm, the use of torture, etc., all of which was officially denied but is now widely accepted as true. Not until the March 1968 My Lai massacre came to light in November 1969 did the western media start to shift its viewpoint more in line with what the Tribunal had revealed.

As for Baldwin, the fact that his name was associated with the Tribunal landed him in some difficulty when he was initially denied entry to the United Kingdom in May, 1967, a story that was picked up by The Observer newspaper. Russell came to his defense with a letter to the editor that was published on June 25, declaring: “To proscribe visas to such eminent literary figures as Mr. Baldwin … is a disgrace to Britain or to any civilized nation. Must they be considered ‘undesirable aliens’ because they cannot be silent about the crimes committed against the people of Vietnam?” On this note, at least, Russell and Baldwin were in full agreement.

As a footnote to this story, it was the need to raise money for the Peace Foundation and the Tribunal that prompted Russell to sell his archives at auction, a move that saw the first instalment of the Bertrand Russell Archives arrive at McMaster University in 1968.

Sources

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1944-1967 (Volume III). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1969. (2) Bertrand Russell. War Crimes in Vietnam. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1967. (3) Bertrand Russell, “Who Is ‘Undesirable’?” The Observer, 25 June 1967, p. 14 (copy in the Russell Archives, C67.15). (4) Nicholas Griffin, ed. The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Public Years, 1914-1970. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. (5) Stefan Andersson, “A Secondary Bibliography of the International War Crimes Tribunal: London, Stockholm and Roskilde.” Russell: the Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies, n.s. 31 (Winter 2011-12): 167-187 (6) Michele Elam, ed. The Cambridge Companion to James Baldwin. Cambridge University Press, 2015. (7) David Leeming. James Baldwin: a biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994.

James Baldwin

January 9, 1967

Dear Bertrand Russell:

I hope you will forgive me for being so tardy in my answer to your letter, but I’ve been travelling. I am happy that you have asked me to be a member of the tribunal and I will be very honored to serve.

While I was in New York, I spoke to James Forman[1], of the Student Non-Violent Co-ordinating Committee, and to Stokeley [sic] Carmichael[2], concerning the tribunal. As you may know, this most senseless and criminal of wars has had a devastating effect on what was once, in good faith, thought of as the American intellectual community. One may not like it – I don’t like it – but it is not enough, these present days, to be an intellectual, especially in America; the logic of one’s honor forces one to become a revolutionary. Well, that means that, in America, we are very much alone. And this is complicated by the role of color in American life. In brief, what seems to paralyze many otherwise active and decent men and women in America is their really chilling suspicion that the crimes being committed in their names in Vietnam have been being committed all along, and in their names, within the borders of the American continent, and to their co-citizens, who are also related to them by blood: the children they are bombing have always been their own. Some of us in America can testify to this, and our testimony is unanswerable. This is why both public officials and private citizens are desperately anxious that the domestic color conflict – which has placed us on the edge of chaos, on the edge of civil war – and the

[second page]

foreign conflict never be connected. Yet, the conflicts are, of course, connected, in only in the mind, for example, of the black boy whose reward for not having been murdered at home is to be sent off to be murdered, in defense of his opressors [sic], in a strange land. And in the name of freedom.

One of the few hopes remaining to America, or indeed to the Western world, is the exposure of this monumental fraud. And Mr. Carmichael and I wish, therefore, that the tribunal would consider inviting a person, for example, as Mrs. Fanny [sic] Lou Hamer[3], of Mississippi, or Mr. James Forman, of SNCC, or even Mrs. Rosa Parks[4] whose sore feet began the Montgomery bus boycott. It is not so much a matter of having their testimony heard as it is a matter of hoping that their testimony can help to turn us back from destruction. None of the problems which plague my unhappy country can even begin to be faced until our criminal intervention in the lives of other nations is brought to a halt.

Mr. Carmichael can be reached at SNCC head-quarters: 36 Nelson Street, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia, or: 1810 Amethyst Street, The Bronx, 62, New York City, NY. The New York phone number, just in case, is 212 (that’s the area code) TA8-9179.

Thank you again for your invitation, and I look forward to hearing from you.

Very sincerely,

[signature]

James Baldwin

c/o Leeming,

Robert College,

Bebek, Istanbul,

Turkey

[1] James Forman (1928-2005) was a leader in the civil rights movement. As Baldwin notes in this letter, Forman was with the SNCC. He was later a leader in the Black Panther Party.

[2] Stokely Carmichael, later Kwame Ture (1941-1998), was, like Forman, a leader in the SNCC and the Black Panthers. He would also serve on Russell’s Tribunal.

[3] Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977) was a leader in the civil rights movement, especially in the areas of voting reform and women’s rights.

[4] Rosa Parks (1913-2005) was a civil rights activist whose 1955 refusal to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Mississippi bus is viewed as one of the founding and defining moments of the civil rights movement.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 10.01, Document 170335. Copyright James Baldwin Estate. Used with permission. All rights reserved. Copy provided for private study only. For any other use, permission of the copyright holder is required.