“I am very sorry … that my objection to your theory of judgment paralyses you”

Ludwig Wittgenstein to Bertrand Russell

July 22, 1913

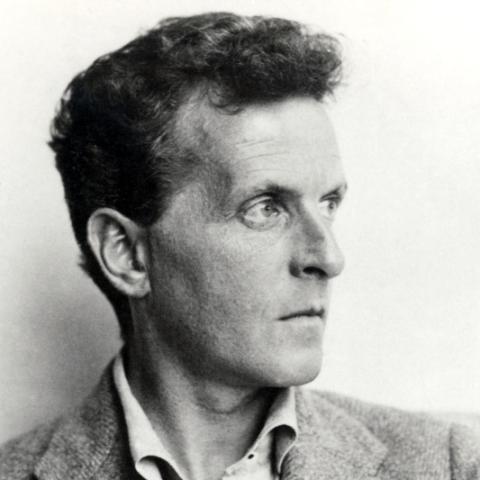

The name Ludwig Wittgenstein is well known today, both for his contributions to philosophy and in the popular imagination as a quintessentially brilliant but difficult and eccentric thinker. However, when Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus was originally published—in German in 1921, and in English in 1922—Bertrand Russell was much better known. In fact, Wittgenstein relied on Russell to get his manuscript published in the first place, and it was Russell’s introduction to the Tractatus that encouraged publishers to consider accepting it at all. While Wittgenstein was grateful for Russell’s efforts, he was dismayed by his introduction, feeling that not even his former professor understood him. For Russell’s part, he was by this time exhausted by his relationship with the young Austrian who had been his student at Trinity in the years leading up to the First World War.

The two had met in October 1911 when Wittgenstein appeared unannounced at Russell’s rooms at Cambridge, interrupting his tea with C.K. Ogden (who, by chance, would later be instrumental in having the Tractatus translated). Wittgenstein had sought out Russell because he had been advised of his eminent intellectual status, and soon the professor and his student were engaged in lively discussions and debates. As Russell recalled in his Autobiography: “He was perhaps the most perfect example I have ever known of genius as traditionally conceived, passionate, profound, intense, and dominating.”

Life with Wittgenstein was not easy. In a November 1911 letter to his lover, Ottoline Morrell, Russell complained that his student was “very argumentative & tiresome.” He was also completely uncompromising and, to say the least, did not suffer fools. In a major understatement, Russell said of Wittgenstein (in his Autobiography): “He was not always easy to fit into a social occasion.” By March 1912, however, Russell had seen enough of Wittgenstein to find hope in his genius, telling Ottoline “I love him & feel he will solve the problems I am too old to solve … He is the young man one hopes for. But as is usual with such men, he is unstable and may go to pieces.” As Russell soon discovered, he was right to be cautious of Wittgenstein.

In the spring of 1913, Russell was embarking on a new work. The monumental Principia Mathematica, written in collaboration with Alfred North Whitehead, had just been published, and Russell was intellectually exhausted by his investigation into mathematics and logic. His new book was to be in the area of epistemology, and in May and June he wrote the bulk of what would become Theory of Knowledge. He decided to show Wittgenstein some of this new work, particularly on the theory of judgment, but was not prepared for his student’s reaction. Wittgenstein’s critical rebuke of Russell’s work left Russell reeling.

The Wittgenstein letter chosen for display here relates to this episode. It was written a couple of months later in the summer of 1913 from Austria, where Wittgenstein was visiting. In the short piece, Wittgenstein’s lack of social awareness is quite evident. He begins with his own philosophical musings, moves to a comment on the weather, and then finally to a very brief reference that he is “very sorry to hear that my objection to your theory of judgment paralyses you.” This would be the extent of Wittgenstein’s apology for the manner in which he had dismissed Russell’s work. Three years later, in 1916, Russell reflected on this experience in a letter to Ottoline: “Do you remember that … I wrote a lot of stuff about Theory of Knowledge, which Wittgenstein criticised with the greatest severity? His criticism, tho' I don't think you realised it at the time, was an event of first-rate importance in my life, and affected everything I have done since. I saw he was right, and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy. My impulse was shattered, like a wave dashed to pieces against a breakwater.” Russell abandoned Theory of Knowledge, and only portions of it were published in journals during his lifetime. The entire manuscript would not appear until it was eventually published in 1983 as volume 7 of the Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell.

Despite this profound setback, or perhaps because of it, Russell was not ready to abandon Wittgenstein. He continued to recognize his student’s brilliance and was determined to have him put his thoughts to paper. When Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge in the fall of 1913, Russell convinced him to dictate his thoughts to a stenographer, with Russell in attendance engaging Wittgenstein in conversation. These ‘Notes on Logic’, available in various drafts in the Russell Archives, would have an impact on Russell’s future work and would also inform Wittgenstein’s own Tractatus.

In the meantime, at the outbreak of war in 1914, Wittgenstein volunteered with the Austrian army; at the end of hostilities, he was a prisoner of war in Italy. Amazingly, he had worked on the manuscript of the Tractatus throughout the war and enthusiastically contacted Russell in March of 1919 to let him know about it. As Russell recounted in his Autobiography: “It appeared that he had written a book in the trenches, and wished me to read it.” Russell arranged for the manuscript to be sent to him. They met to discuss the work at The Hague in 1919 when it was agreed that Russell would write the introduction. Later, after Wittgenstein’s efforts to have the Tractatus published failed, Russell used his connections to find a publisher.

Meanwhile, Russell was becoming concerned about Wittgenstein’s growing religiosity, and Wittgenstein was never hesitant about criticizing Russell’s work or lifestyle. In 1929, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge to complete his Ph.D., where Russell was, reluctantly, one of his examiners. They had little to do with each other thereafter.

There are over 50 letters from Wittgenstein to Russell in the Russell archives, several of which are published in Russell’s Autobiography.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1914-1944 (Volume II). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1968; includes the 1916 letter to Ottoline Morrell. (2) Ronald W. Clark. The Life of Bertrand Russell. Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975; includes quotes from the 1911 and 1912 letters to Ottoline Morrell. (3) Nicholas Griffin, ed. The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Private Years, 1884-1914 and The Public Years, 1914-1970. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. (4) Brian McGuinness, ed. Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents, 1911-1951. Blackwell Publishing, 2008. (5) Ray Monk, Ludwig Wittgenstein: the Duty of Genius. Vintage, 1991. (6) Elizabeth Ramsden Eames, ed., in collaboration with Kenneth Blackwell. The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, Volume 7: Theory of Knowledge, the 1913 Manuscript. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1984. (6) The ‘Notes on Logic’ drafts in the Russell Archives can be found in Box 5.56, Documents 057822, 057823, and 057824.

22.7.13[1]

HOCHREIT

POST HOHENBERG

N.-Ö[2]

Dear Russell,

Thanks for your kind letter.[3] My work goes on well; every day my problems get clearer now & I feel rather hopefull [sic]. All my

[second page]

progress comes out of the idea that the indefinables of Logic are of the general kind (in the same way as the so called Definitions of Logic are general) & this again comes from the abolition of the real variable. Perhaps you laugh at me for feeling so sanguine at present; but although I have not solved one of my problems I feel very, very much nearer to the solution of them all than I ever felt before.

The weather here is constantly

[third page]

rotten, we have not yet had two fine days in succession. I am very sorry to hear that my objection to your theory of judgment paralyses you. I think it can only be removed by a correct theory of propositions. Let me hear from you soon. Yours ever, etc.

L.W.

[1] 22 July 1913

[2] Nieder-Österreich, Austria

[3] Russell’s letter to Wittgenstein is not available in the Russell Archives.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 5.56, Document 057736. Public domain in Canada. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, the user assumes all risk.