“I imagine that we must apply to the Royal for a grant”

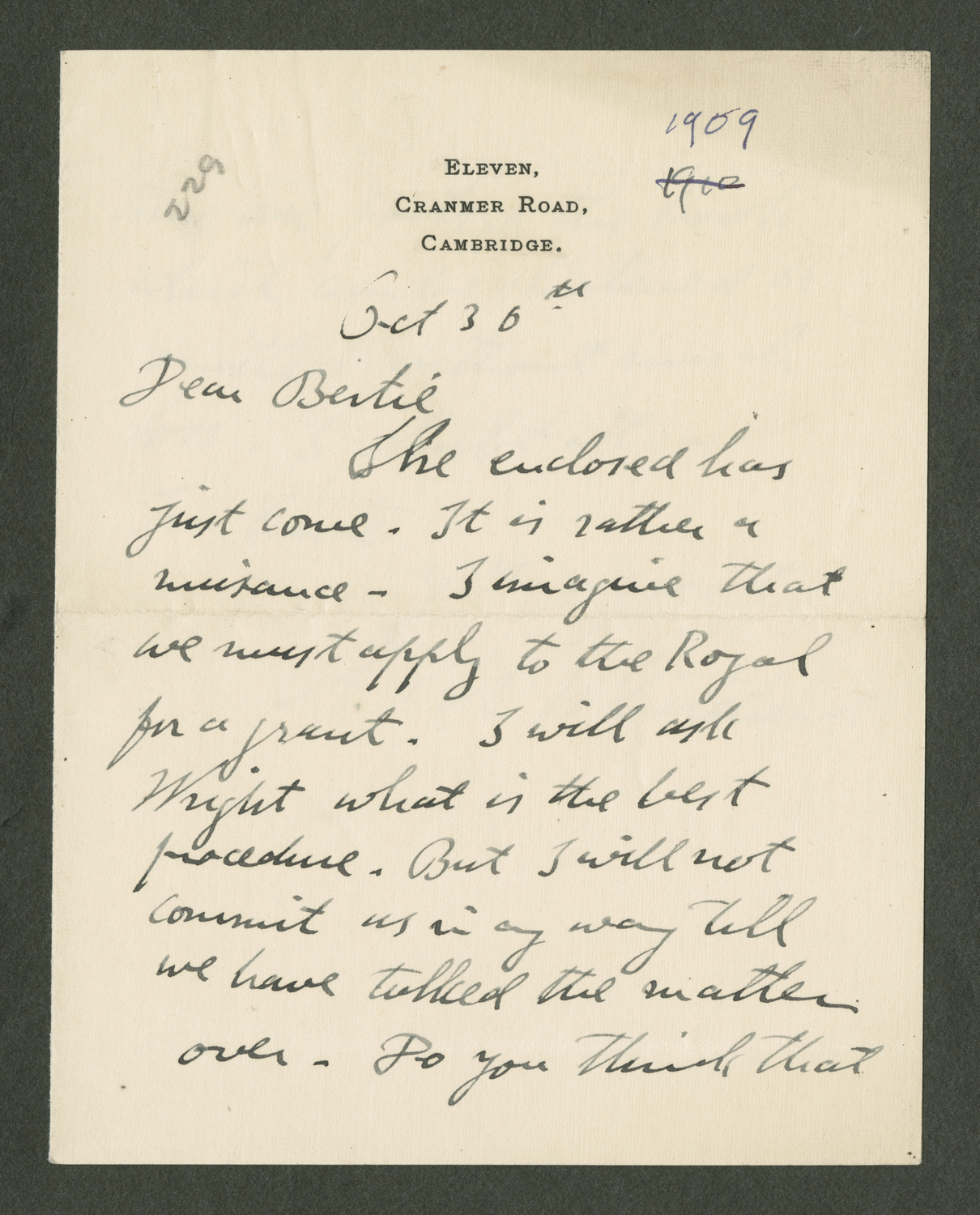

Alfred North Whitehead to Bertrand Russell

October 30, 1909

In 1889, Russell was awarded a scholarship to Trinity College, Cambridge. The process by which the scholarship was granted involved an examination. Russell’s examiner was Alfred North Whitehead (1861-1947), a man who would play a very significant role in Russell’s life, first as a mentor, then as a colleague, friend, and collaborator. Whitehead instantly recognized Russell’s great intellect and enthusiastically endorsed him for the scholarship. When Russell enrolled at Trinity as a freshman in October 1890, Whitehead went out of his way to ensure that Russell met all of the other like-minded students and later recommended his election to the Apostles, an elite intellectual group. Russell had a deep admiration for his mentor. As he recalled in his Autobiography: “Whitehead was extraordinarily perfect as a teacher. He took a personal interest in those with whom he had to deal …. He would elicit from a pupil the best of which a pupil was capable. He was never repressive, or sarcastic, or superior, or any of the things that inferior teachers like to be. I think that in all the abler young men with whom he came in contact he inspired, as he did in me, a very real and lasting affection.”

In 1894, Russell married Alys Pearsall Smith, and they would soon become friends with Whitehead and his wife, Evelyn. They would often pay extended visits to each other and even lived together for a short while. In the summer of 1900, the two couples visited Paris where Russell and Whitehead attended the International Congress of Philosophy. It was here that Russell met the Italian mathematician, Giuseppe Peano, which Russell described as “a turning point in my intellectual life.” A few months later, after exhaustively studying Peano, Russell “sat down to write The Principles of Mathematics, at which I had already made a number of unsuccessful attempts.” He completed the work in 1902, and it was published the following year. Almost immediately after finishing the manuscript, Russell “devoted myself to the mathematical elaboration which was to become Principia Mathematica. By this time I had secured Whitehead’s cooperation in this task.”

The writing of Principia Mathematica by Russell and Whitehead was one of the most outstanding intellectual achievements in the 20th century. It was also an extremely daunting task—it took the pair ten years to complete the work. The first several years were spent in research, discovery, and working out problems, so that by 1907, as Russell noted, “it only remained to write the book out.” Russell thereafter wrote for 10 to 12 hours a day, 8 months of the year. He commented: “The manuscript became more and more vast, and every time that I went out for a walk I used to be afraid that the house would catch fire and the manuscript would get burnt up. It was not, of course, the sort of manuscript that could be typed or even copied. When we finally took it to the University Press, it was so large that we had to hire an old four-wheeler for the purpose.” After receiving the manuscript, the Cambridge University Press wrote to Whitehead to express concern about the challenges in publishing the work. This prompted Whitehead to write the letter to Russell that is displayed here.

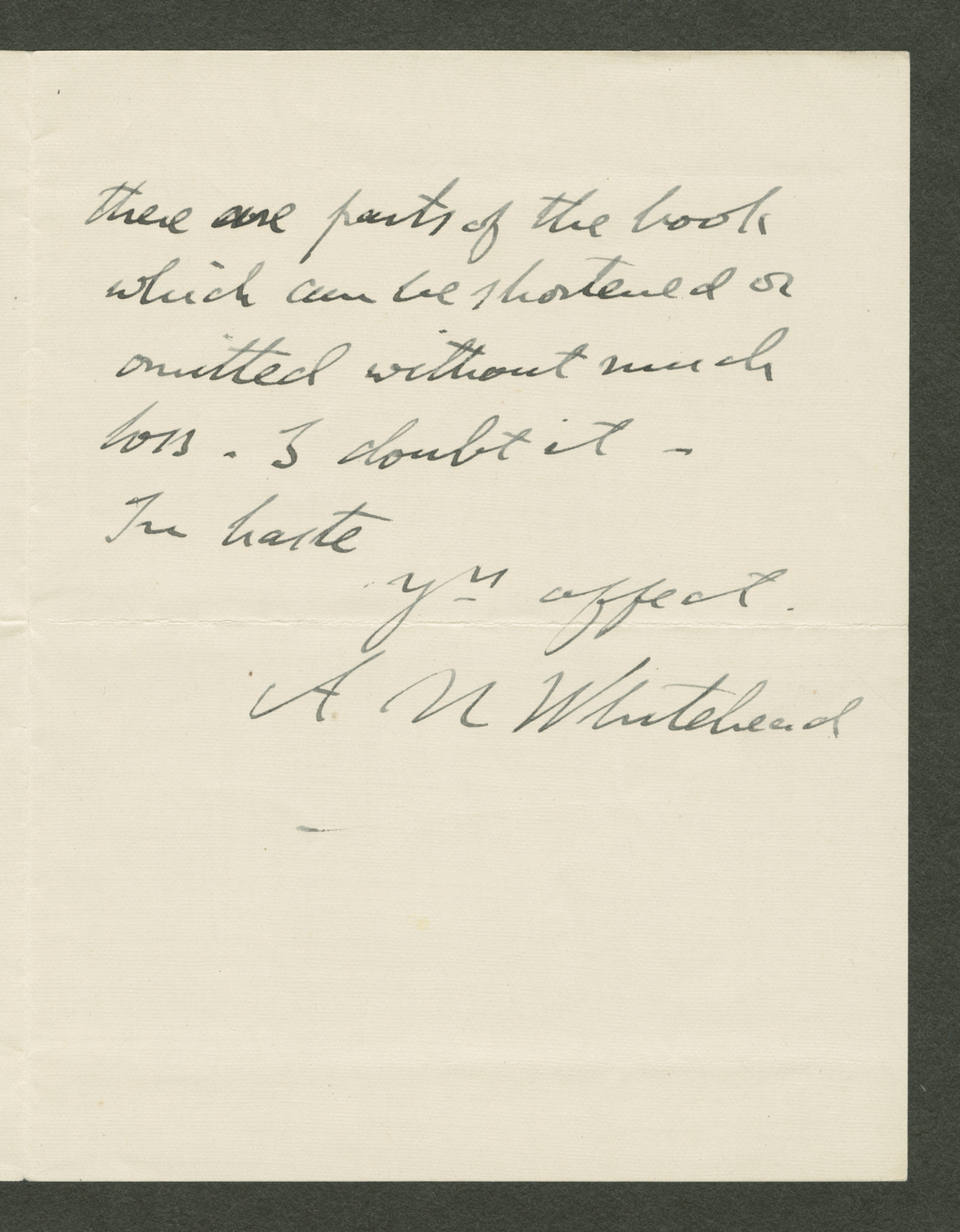

The challenge facing the Press was that the publication of Principia Mathematica would result in a loss of £600, and they would not able to suffer a loss greater than £300. As Whitehead states in the letter: “I imagine that we must apply to the Royal for a grant.” Indeed, they did successfully apply to the Royal Society and received a grant of £200, but this still left them short £100. Russell quipped: “the remaining £100 we had to find ourselves. We thus earned minus £50 each by ten years’ work. This beats the record of Paradise Lost.” The three-volume work would be published over a three-year period from 1910 to 1913. After its completion, Russell was drained: “my intellect never quite recovered from the strain. I have been ever since definitely less capable of dealing with difficult abstractions than I was before. This is part, though by no means the whole, of the reason for the change in the nature of my work.”

Russell and Whitehead would thereafter gradually drift apart. The Whiteheads did not agree with Russell’s pacifist stance during the First World War—their two sons served in the military, and the younger one was killed. In 1924, Whitehead accepted a position at Harvard, thus adding a physical distance to his relationship with Russell. Whitehead also moved intellectually from mathematics to a more metaphysical philosophy that included a religious component that Russell could not accept. Despite these differences, however, as Russell observed, “we went our separate ways, though affection survived to the last.”

There are approximately 100 letters from Whitehead in the Russell archives. The last is from 1944 congratulating Russell on his return to Trinity College. Unfortunately, Whitehead’s own papers, including Russell’s letters to him, have not survived—at Whitehead’s request, his papers were destroyed after his death in 1947.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1872-1914 (Volume I) and 1914-1944 (Volume II). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1967 and 1968. (2) Ronald W. Clark. The Life of Bertrand Russell. Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975.

ELEVEN,

CRANMER ROAD,

CAMBRIDGE.

Oct 30th[1]

Dear Bertie

The enclosed has just come.[2] It is rather a nuisance – I imagine that we must apply to the Royal[3] for a grant. I will ask Wright what is the best procedure. But I will not commit us in any way till we have talked the matter over – Do you think that

[second page]

there are parts of the book which can be shortened or omitted without much loss – I doubt it –

In haste

Yrs affect.[4]

A.N. Whitehead

[1] The year was 1909.

[2] The enclosure was a letter from Richard Wright of Cambridge University Press dated 29 October 1909. It can be seen in the Russell archives with the publishing correspondence, box 1.21.

[3] The Royal Society. Whitehead and Russell did receive a grant, but it still left them short.

[4] “Yours affectionately”, Whitehead’s typical closing in letters to Russell.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 5.54, Document 057431. Public domain in Canada. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, the user assumes all risk.