“Forgive this desolation…”

H.G. Wells to Bertrand Russell

May 20, 1945

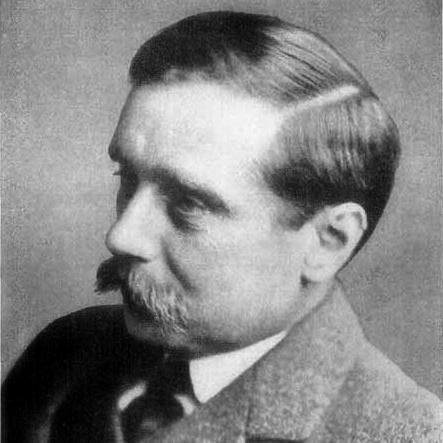

In his Autobiography, Russell recounts his first meeting with H.G. Wells (1866-1946): “…in 1901 I became a member of a small dining club called ‘The Coefficients’, got up by Sidney Webb for the purpose of considering political questions from a more or less Imperialist point of view. It was in this club that I first became acquainted with H.G. Wells, of whom I had never heard until then.” In hindsight it may seem rather surprising that Russell had not yet heard of Wells, for he was already the celebrated author of such novels as The Time Machine (1895), The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896), The Invisible Man (1897), and The War of the Worlds (1898). However, if nothing else, their backgrounds would have kept them apart. Russell was an aristocrat with a private income immersed in the study of mathematics and philosophy at Cambridge, while Wells came from the working class and made his living as a prolific and popular writer of both fiction and non-fiction. But they found common ground in The Coefficients, bridling against the imperialist leanings of their fellow members.

In Experiment in Autobiography, Wells put his own spin on how he and Russell reacted to the club. “There was an argument at which unfortunately I was not present.” Some of the members “declared themselves fanatical devotees of the Empire.… Russell said that there were a multitude of things he valued before the Empire. He would rather wreck the Empire than sacrifice freedom. So if this devotion was what the club meant—! And out he went—like the ego-centred Whig he is—without consulting me.” While Wells agreed with Russell’s anti-imperialist views, he remained in the club. “The more this Imperialist nonsense was talked about in the club, the more was it necessary that one voice at least should be present to contradict it.”

In the years leading up to the First World War, Russell found much to admire in his new, socialist acquaintance—at least politically—as they both spoke out against the impending hostilities. On the personal front, however, there was less connection. It seems that Wells, despite his socialism, was pleased to have people of Russell’s background in his circle and was eager to impress. In Portraits From Memory, Russell relates an anecdote that suggests this (and also suggests a Russell bias): “As a result of the political sympathy between us, I invited Wells and Mrs. Wells to visit me at Bagley Wood, near Oxford, where I then lived. The visit was not altogether a success. Wells, in our presence, accused Mrs. Wells of a Cockney accent, an accusation which (so it seemed to me) could more justly be brought against him.” Also in those pre-war days, Russell took a moralistic tone towards Wells’ affairs with women, which were sometimes very public. A great scandal occurred in 1909 when Wells’ young lover, Amber Reeves, gave birth to a child. Writing at the time to his friend, Lucy Donnelly, Russell called Wells “an unmitigated cad and scoundrel.”

A much more serious rupture in their relationship occurred when the war finally broke out in 1914. Wells retracted his earlier stance and immediately supported the British war effort. In fact, in the first days of the war he penned the popular catchphrase “the war that will end war.” While the words were intended as a means of justifying the war, they have since become associated with the disillusionment that the war brought forth. Wells would experience his own disillusionment with the war, recounted in his novel Mr. Britling Sees It Through (1916). In the meantime, however, the pacifist Russell had no time for Wells, and Wells had no time for Russell.

After the war, however, Wells’ committed and deepening socialism caught Russell’s eye, and the two were soon on friendlier terms. They both had a keen interest in education reform, and Russell solicited Wells’ support for Beacon Hill, the experimental school that he and his wife, Dora, opened in 1927. Wells’ Outline of History—greatly admired by Russell—would form the basis of the school’s history lessons. Russell also grew more understanding of Wells’ romantic entanglements, if for no other reason than he was having many of his own. (Ironically, Russell even came close to having his own affair with Wells’ former lover, Amber Reeves). When Russell learned in 1926 that Wells and Dora had had a brief affair in 1924, he was not bothered. He likewise displayed tolerance towards Wells when he was contacted by the writer Rebecca West who was seeking Russell’s advice and support concerning her son, Anthony, the offspring of her affair with Wells.

That understanding and even affection became especially evident in 1945 when Russell learned that Wells was quite ill. By this time, Russell had been back at Trinity College, Cambridge for a year, having returned from a trying six years in the United States. He wrote to Wells on May 15: “I am so sorry to hear that you have not been well. I had been looking forward to seeing you.” Wells enthusiastically replied five days later with the letter on display here. He begins: “I was delighted to get your friendly letter.” He then goes on to talk politics—“I get more & more anarchistic and ultra left as I grow older”—and his health—“I have been ill and I keep ill.” He then catches himself and concludes with “Forgive this desolation. I hope to see you both before very long & am yours most gratefully.” Russell wrote again promptly on May 26: “Your personal news is sad, & much distresses me. And the state of the world is not such as to inspire in you a wish for prolongation of a painful life. If it is not too much effort for you, I should very much like to see you.” He signs the letter, “with warm friendship”. Russell would visit Wells in early June. Afterward, Russell confided in a letter to a friend, Peggy Kiskadden: “I went to see H.G. Wells the other day, and found him apparently dying, without any vigour of either mind or body. It was sad.” Wells died the following spring.

In writing about Wells ten years later in Portraits From Memory, Russell, while not without criticism, was full of praise. Wells, he wrote, “was one of those who made Socialism respectable in England. He had a very considerable influence upon the generation that followed him, not only as regards politics, but also as regards matters of personal ethics…. Wells’s importance was primarily as a liberator of thought and imagination. He was able to construct pictures of possible societies, both attractive and unattractive, of a sort that encouraged the young to envisage possibilities which otherwise they would not have thought of.”

Two H.G. Wells letters, including the one displayed here, are published in Russell’s Autobiography.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1872-1914 (Volume I), and 1914-1944 (Volume II). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1967 and 1968. (2) Bertrand Russell. Portraits From Memory and Other Essays. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1956. (3) David Smith, ed. The Correspondence of H.G. Wells. Volume 4, 1935-1946. London: Pickering & Chatto, 1998 (4) H.G. Wells, Experiment in Autobiography. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934. (5) Norman and Jeanne MacKenzie. The Life of H.G. Wells, the Time Traveller. London: Hogarth Press, 1987. (6) Nicholas Griffin, ed. The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Private Years, 1884-1914 and The Public Years, 1914-1970. London and New York: Routledge, 2002; includes the quotes from Russell’s letters to Donnelly and Kiskadden. (7) Letters from Russell to Wells, May 15 and May 26, 1945 (copies in Bertrand Russell Archives, RA3 57).

13, HANOVER TERRACE, REGENT’S PARK, N.W.1.

TELEPHONE, PADDINGTON 6204

May 20th, ‘45

My dear Russell,

I was delighted to get your friendly letter.[1] In these days of revolutionary crisis it is incumbent upon all of us who are in any measure influential in left thought to dispel the tendency to waste energy in minor dissentions & particularly to counter the systematic and ingenious work that is being done to sabotage left thought under the cloak of critical reasonableness. I get a vast amount of that sort of propaganda in my letter box. I get more & more anarchistic and ultra left as I grow older. I enclose a little article “Orders is Orders” that the

2

New Leader has had the guts, rather squeamish guts, to print at last.[2] What do you think of it?

We must certainly get together and talk (& perhaps conspire) & that soon. What are your times & seasons? My daughter in law Marjorie fixes most of my engagements so you & Madame must come to tea one day & see what we can do.

I have been ill and I keep ill. I am President of the Diabetes Soc’y & diabetes keeps one in & out, in & out of bed every two hours or so. This exhausts, and this vast return to chaos which is called the peace, the infinite meanness of great masses of my fellow creatures, the wickedness of organized religion give me a longing for a sleep that will have no awakening. There is a long history of heart failure on my paternal side but modern palliatives are

3

very effective holding back that moment of release. Sodium bicarbonate keeps me in a grunting state of protesting endurance. But while I live I have to live and I owe a lot to a decaying civilization which has anyhow kept alive enough of the spirit of scientific devotion to stimulate my curiosity [and] make me its debtor.

Forgive this desolation. I hope to see you both before very long & am yours most gratefully.

H.G. Wells

[1] Russell had written to Wells on May 15 to express his sorrow over Wells’ illness.

[2] “The piece he sent Russell was ‘Orders is Orders: A Vanishing Excuse in a New World,’ The New Leader, 19 May 1945, p. 5.” (David Smith, ed. The Correspondence of H.G. Wells. Volume 4, 1935-1946. London: Pickering & Chatto, 1998, p. 524). In his reply of May 26, Russell wrote: “I read it with a feeling that it would be a better world if people would listen to you.”

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 5.53, Document 056279. Public domain in Canada. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, the user assumes all risk.