“I want to write you a cross letter”

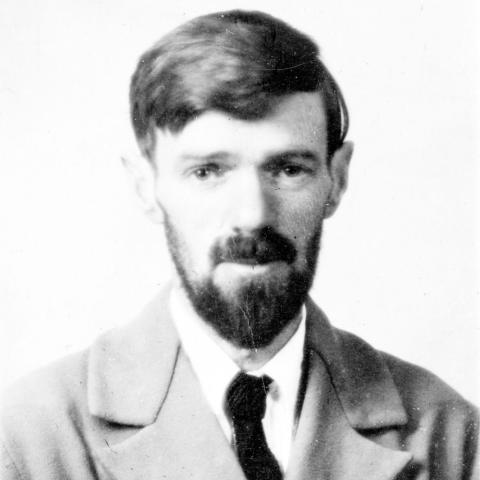

Frieda Lawrence and D.H. Lawrence to Bertrand Russell

February 24, 1916

In 1936, Russell sold the 23 letters in his possession from D.H. Lawrence to one Harry Wells. Lawrence had died in 1930, and Wells, a Harvard student, was collecting letters for a planned biography that was never completed. Russell was willing to sell the letters because he had recently married his third wife, Patricia ‘Peter’ Spence, and was in need of funds to support them both. As part of the sale agreement, Russell received typed copies of the letters in return. These copies are available in the Russell archives, while the original Lawrence letters eventually ended up at the University of Texas at Austin. Accordingly, there are no original Lawrence letters in the Russell archives. There is, however, an original letter from Lawrence’s wife, Frieda, to which Lawrence has added a short postscript. That letter has been chosen for display here.

The letter, dated February 1916, is from the very end of the short and acrimonious Russell-Lawrence friendship. While the letter concludes with both Frieda and Lawrence expressing the hope that Russell will visit them at their new home in Cornwall, the tone of the bulk of the letter conveys the animosity that the Lawrences felt towards Russell at that time. Frieda states that she wished to write “a cross letter”, that Russell does not “care for anybody”, and that his “social democratic ideal” is “a stale old bun.” What had transpired over the previous year to bring them to this point?

Russell and D.H. Lawrence had met in February 1915 through Russell’s lover, Ottoline Morrell, who felt they would have much in common. On the surface, that might have seemed unlikely. Russell, then 42 years old, was from one of Britain’s best known aristocratic families and was an established academic at Cambridge. Lawrence, the son of a coal miner, was just 29 years old, and while his early published works—including the novel Sons and Lovers—were well-received, his novel Rainbow would be suppressed for obscenity later in 1915, and he would find it difficult to earn a living for several years.

What they did have in common, however, was an opposition to the First World War which was then unfolding, and an initial mutual admiration. As Russell stated in his Autobiography: “Pacifism had produced in me a mood of bitter rebellion, and I found Lawrence equally full of rebellion. This made us think, at first, that there was a considerable measure of agreement between us.” But then Russell added: “it was only gradually that we discovered that we differed from each other more than either differed from the Kaiser.”

The unravelling of their friendship began when they attempted to collaborate on a series of lectures that would offer a new vision of society. Lawrence almost immediately rejected Russell’s contributions to the project, while Russell was dumbfounded by Lawrence’s hostile reaction. At the time, Lawrence was developing his ‘blood-consciousness’ philosophy, which, with its emphasis on physicality and instinct, could not have been more antithetical to Russell’s intellectual style. Initially, Lawrence caused Russell some self-doubt. As Russell wrote years later in his Autobiography: “I felt him to be a man of a certain imaginative genius, and, at first, when I felt inclined to disagree with him, I thought that perhaps his insight into human nature was deeper than mine.” He added: “I was already accustomed to being accused of undue slavery to reason, and I thought perhaps that he could give me a vivifying dose of unreason.” At one point, Russell’s agony over Lawrence’s antagonism led him to think “that I was not fit to live and contemplated suicide.”

Their disagreements intensified and the collaborative project was abandoned. The following year, however, Russell would present his own series of lectures in London. They were very well received and were published as The Principles of Social Reconstruction. While Russell conceded that the book “was better than it would have been if I had not known” Lawrence, his ultimate summation of Lawrence was vicious. Of his ideas, Russell wrote: “His thought was a mass of self-deception masquerading as stark realism” and “his ideas cannot be too soon forgotten.” In fact, Russell believed that Lawrence’s philosophy of ‘blood-consciousness” was a forerunner of fascism. “This seemed to me frankly rubbish, and I rejected it vehemently, though I did not then know that it led straight to Auschwitz.”

For his part, Lawrence would go on to pillory Russell in his novel Women In Love (1920) as the character Sir Joshua Malleson (or Mattheson in some editions), “a learned, dry Baronet of fifty, who was always making witticisms and laughing at them heartily in a harsh, horse-laugh.” As a character observes: “Did you ever see anything like Sir Joshua? But really, …he belongs to the primeval world, when great lizards crawled about.”

Unfortunately, none of Russell’s letters to Lawrence have survived. To no one’s surprise, however, he never took up the Lawrences’ invitation to visit them in Cornwall.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1914-1944 (Volume II). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1968. (2) Nicholas Griffin, The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Public Years, 1914-1970. Routledge, 2001; Griffin discusses the sale of the Lawrence letters on p. 337 fn 1, and p. 338 fn 1. (3) George J. Zytaruk and James T. Boulton, eds. The Letters of D.H. Lawrence, Volume II. Cambridge University Press, 1981; the 23 letters sold by Russell had originally been published in a 1948 edition by Gotham Book Mart, edited by Harry T. Moore.

Porthcothan,

St. Merryn,

North Cornwall[1]

[Feb. 1916][2]

Dear Mr. Russell,

I want to write you a cross letter – you said to Lawrence that you are not very happy – I don’t see how you could be – you told me to say to Lawrence that you loved him – yet I don’t feel that you care for him – I don’t think you care for anybody or if you do it is in a most unsatisfying way. And your belief in your social democratic ideal is not vital to you, it seems mostly obstinancy.[3] It is a stale old bun even to you. Lawrence is better and I felt very sure and happy lately of a life that can be lived with meaning and dignity and even happiness – We have found such a nice place and I am looking forward to living there. A few people will come and stay from time to time and I hope you will be one of them. There won’t be many I know to my sorrow – I know you have not a high opinion of me[4] but that is because I don’t believe in what

[second page]

you put your trust in– And I have a great respect for you ultimately and I wish you would come and stay with us soon for a little while and we would be happy.

Yours sincerely,

Frieda Lawrence

Our new address is:

The Tinners Arms

Zennor

near St. Ives

Cornwall

We leave here on Tuesday (29th Feb.).[5] Our address is then “The Tinners Arms, Zennor, St. Ives, Cornwall.” It is very lovely at Zennor. Come down there when you are free, won’t you? And give up your London flat when the lease is up.

D.H.L.

[1] This address appears as embossed letterhead on the original letter. It is difficult to see in the scanned version.

[2] The date of ‘Feb. 1916’ appears to have been added by Russell. A more precise date of 24 February 1916 is contained in Lawrence’s published letters: The Letters of D.H. Lawrence, Volume II (Cambridge University Press, 1981), edited by Zytaruk and Bolton.

[3] Frieda appears to be referring to Russell’s intended contribution to the aborted lecture series he and Lawrence had been planning.

[4] Frieda was right, Russell did not have a high opinion of her. He would later write in his Autobiography: “she imbibed prematurely the ideas afterwards developed by Mussolini and Hitler, and these ideas she transmitted to Lawrence.”

[5] Postscript added by D.H. Lawrence.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 5.27, Document 052050. Public domain in Canada. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, the user assumes all risk.