“you … would be entirely free”

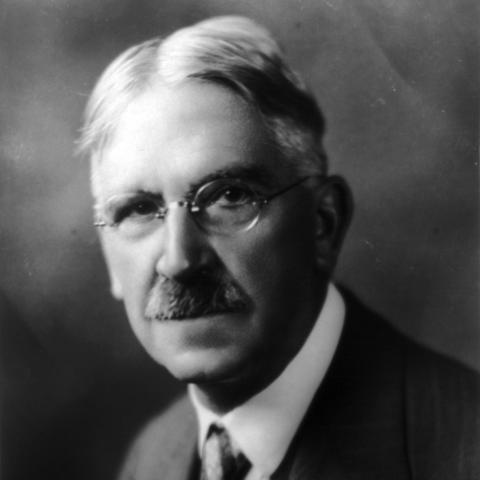

John Dewey to Bertrand Russell

May 27, 1940

The aborted appointment of Bertrand Russell to the College of the City of New York early in 1940 became a rallying point for academics across the United States (see the introduction to the Vera Brittain letter for background). The national council of the American Association of University Professors even established an Academic Freedom-Bertrand Russell Committee. One of the leaders of the protest was John Dewey (1859-1952) who, now in his early 80s, was the recognized dean of American philosophers. He was so taken up with Russell’s plight that he edited a series of essays under the title The Bertrand Russell Case that was published in 1941. When all attempts to have Russell’s CCNY appointment upheld ended in failure, Dewey then went one step further by helping to arrange an appointment for Russell as a lecturer at the Barnes Foundation in Merion, Pennsylvania, near Philadelphia.

The Foundation was the pet project of the eccentric millionaire, Dr. Albert C. Barnes. He had acquired one of the finest private art collections in the world and then hired staff to present lectures on art appreciation and other subjects to a select group of students. Dewey had lectured at the Foundation in the past, and in this letter of May 27, 1940, he told Russell that he had just met with Barnes who was interested in having Russell join the Foundation on what were very generous terms, with no limitations on what he would teach—“ you … would be entirely free.” In his reply, Russell asked Dewey to “please accept my warmest thanks for your letter and for your generous activity on my behalf.” He soon accepted a five-year contract at the Foundation with an annual salary of $6,000 to teach a course on the history of philosophy. Late in 1940, Russell, his wife, Peter, and their son, Conrad, moved into a house near Philadelphia that Barnes had arranged for them, and Russell began his lectures in January 1941. His fortunes had seemingly taken a positive turn.

Dewey’s efforts on Russell’s behalf are all the more impressive since the two did not see eye to eye on philosophical matters and, even more significantly, did not like each other very much. By the time of this letter, they had known each other for 25 years, having met for the first time in 1914 when Russell was visiting professor at Harvard. They became acquainted again in 1921 in China where both were guest lecturers. At that time, Russell wrote to Ottoline Morrell: “The Americans sprawl all over this place, all convinced of their own righteousness. … The Deweys … are as bad as anybody—American imperialists … and unwilling to face any unpleasant facts. In 1914 I liked Dewey better than any other academic American; now I can’t stand him.” Meanwhile, Dewey felt that Russell disdained people outside his aristocratic class and that he even had a streak of cruelty. However, the manner in which Russell was treated in the United States in 1940 was too much for Dewey to bear. At the end of the CCNY case, he wrote: “As Americans we can only blush with shame for this scar on our repute for fair play.”

As it turned out, Russell’s tenure at the Barnes Foundation was short lived. Barnes was known for being irascible, controlling, dictatorial, and petty. As Russell described him: “Dr. Barnes was a strange character. He had a dog to whom he was passionately devoted and a wife who was passionately devoted to him. … He demanded constant flattery and had a passion for quarrelling.” Fortunately, Russell went to the Foundation with his eyes wide open. “I was warned before accepting the offer that he always tired of people before long. … On December 28th, 1942, I received a letter from him informing me that my appointment was terminated as from January 1st.” Trouble had been brewing for a while, in part because of tensions between Barnes and Peter. It all came to a head over, of all things, Peter’s knitting. Peter used to drive Russell from their house to the Foundation whenever he had to lecture, and she used to sit in the back of the classroom, knitting, while Russell conducted the class. Barnes objected and had Peter banned from the building. Russell had no choice but to support Peter, so the writing was on the wall.

Once again Russell was unemployed. His American sojourn that had started so well at the University of Chicago in 1938 had been in steady decline since then. He hated the University of California, where he had gone in 1939, and his attempted escape to New York had ended in a farce. Now there was the Barnes fiasco. Fortunately, the notoriety that Russell had acquired during the CCNY case had now abated, and he was able to get short term lecture appointments, including at Bryn Mawr (where he saw much of English professor, Edith Finch, who would later become his fourth, and last wife), and then a short appointment to Princeton where he enjoyed weekly meetings with Albert Einstein. Then in December 1943 came some very welcome news from England—Trinity College, Cambridge, was inviting him back to lecture, finally righting the wrong it had done in 1916 when it had dismissed Russell from his lectureship for his anti-war position. Russell gratefully accepted. Because travel was restricted during the Second World War, Peter and Conrad sailed home on one ship, and Russell on another. They all arrived safely in 1944. Russell’s ship docked in June, just after D-Day—even the outlook of the war was bright.

Meanwhile, Russell successfully sued Barnes for his dismissal and was awarded a $20,000 settlement. A silver lining of the Barnes episode was the publication in 1945 of Russell’s A History of Western Philosophy, based in part on his Barnes Foundation lectures. The book, Russell noted, “began by accident and proved the main source of my income for many years. I had no idea, when I embarked upon this project, that it would have a success which none of my other books have had, even, for a time, shining high upon the American list of Best Sellers.” Still widely available today, it remains Russell’s best known and most widely read work. Without the Barnes’ appointment, and without John Dewey’s efforts in gaining the appointment, it might never have been written at all.

Russell does not mention Dewey in the narrative of his Autobiography though he does see fit to publish one of the supportive letters he received from Dewey at the time of the CCNY case.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1914-1944 (Volume II). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1968. (2) Ronald W. Clark. The Life of Bertrand Russell. Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975; includes the quote from Russell’s letter to Ottoline Morrell and Dewey’s quote at the end of the CCNY case. (3) Nicholas Griffin, ed. The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell: The Public Years, 1914-1970. London and New York: Routledge, 2002; includes Russell’s thank you letter to Dewey.

1 West 89, NY City, May 27, ‘40

Dear Mr. Russell,

Thanks for your note. Let me first say that I have engaged in it enough myself so that I am not much bother [sic] by being involved in it unfavorably.

Coming to a more important matter, I spent a day with Dr. Albert C. Barnes in Merion, near Philadelphia. He is the founder and head of the Barnes Foundation, the best collection of modern pixtures [sic] in the US, probably the world. It has a charter as an educational institution from the State of Pennsylvania, the same kind of broad charter as for example the Univ[ersity] of Penn[sylvania]. He told me he would be glad to have the Foundation offer you a salary of $6,000 a year as a lecturer there, term to begin at whatever time next year is convenient to you, and on whatever subject you may choose, hours per week etc., to suit you wishes. While the work done there is primarily along the lines of the arts, there is no limitation in its charter, and you, as I just said, would be entirely free.

I had intended to talk over the matter with Randall[1], the sec[retar]y of the local committee here, before writing you, but as he happened to be out of town and I am writing to you, it seems as well to tell you now, especially as while the proposal is positive, it does not require an immediate answer from you. Dr. Barnes would of course make the offer in official form if you are interested in accepting.

There is a personal matter I should mention. I didn’t mention in my letter to him how it was I happened to see a copy—in part—of his letter to you, and his reply to me (in which by the way he expressed his hope he would be your official host at Harvard next academic year) indicated he has formed

2.

a wrong opinion of your part in the matter. I have now done what I should have done in my first letter, told him just how it came about, namely in a discussion with Randall of your future from the financial point of view.

Very sincerely yours,

John Dewey

[1] John Herman Randall, Jr., professor of philosophy at Columbia University, and secretary of the Academic Freedom-Bertrand Russell Committee, established by the national council of the American Association of University Professors.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 6.32, File 8. Public domain in Canada. Copy provided for personal and research use only. For any other use, the user assumes all risk.