"I am ambitious for you, my dearest Boy"

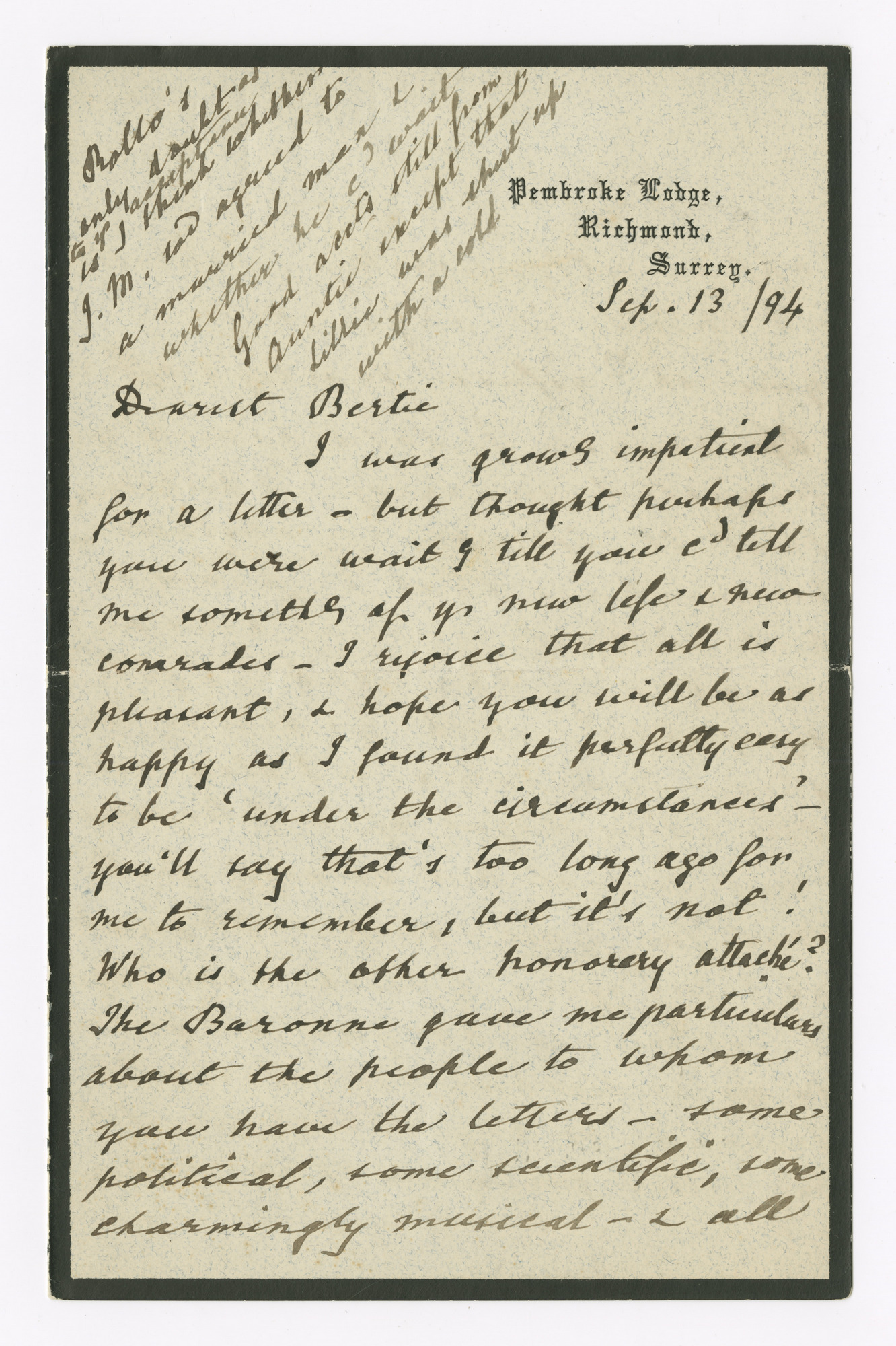

Frances Russell (Granny) to Bertrand Russell

September 13, 1894

In 1874, two-year-old Bertrand Russell and his older sister, Rachel, were visiting their grandparents, Lord John Russell (1st Earl Russell) and Frances, Countess Russell, at Pembroke Lodge, Richmond Park, when Queen Victoria paid a visit—Lord Russell had earlier been her Prime Minister. According to young Bertie’s Aunt Agatha, Bertie “made a nice little bow—but he was much subdued and did not treat Her Majesty with the utter disrespect I expected.”

On a far more serious note, back home in Wales, Bertie’s older brother, Frank, had come down with diphtheria. The two younger children were kept at Pembroke until it appeared that Frank had recovered. Unfortunately, he was, in fact, still contagious when Bertie and Rachel returned home. Rachel soon became ill, followed by her mother. They died within a week of each other in the summer of 1874. Just over a year later, Bertie’s father died, seemingly of a broken heart, though the official cause was bronchitis. Bertie, a few months shy of his fourth birthday, was an orphan.

Bertie’s parents, Lord Amberley (John Russell) and Lady Amberley (Kate Stanley), were, as Bertie wrote years later in his Autobiography, “ardent theorists of reform and prepared to put into practice whatever theory they believed in.” His father “was a disciple and friend of John Stuart Mill” from whom he “learned to believe in birth-control and votes for women.” His mother “sometimes got into hot water for her radical opinions.” Before his death, Amberley had chosen two men to serve as guardians to his two sons—one was a family friend, the other had been Frank’s tutor; both were atheists. Bertie’s grandparents might have accepted this situation but they soon discovered that the tutor had had an affair with Bertie’s mother. However, it was not an affair in the usual sense of the word—the tutor had a chronic illness that impeded his ability to live a normal life and, in an act of charity, Lady Amberley shared her bed with him with the full support of her husband. Bertie’s grandparents were appalled. They intervened to prevent the guardianship from occurring, and Bertie went to live with them in February 1876. Bertie’s grandfather died two years later, leaving Bertie to be raised by his grandmother, the formidable Countess Russell.

According to Bertie, his grandmother—whom he called Granny—“was the most important person to me throughout my childhood. She was a Scotch Presbyterian, Liberal in politics and religion … but extremely strict in matters of morality. … She demanded that everything should be viewed through a mist of Victorian sentiment.” In reflecting on his childhood, Bertie noted that “her great affection for me, and her intense care for my welfare, made me love her and gave me that felling of safety that children need.” As he grew older, however, his feelings changed: “After I reached the age of fourteen, my grandmother’s intellectual limitations became trying to me, and her Puritan morality began to seem to me to be excessive.” In order to keep his thoughts—especially about religion—secret from Granny and other family members, the teenage Bertie wrote diary entries using Greek characters and labelled the book “Greek Exercises.”

Bertie had reason to be wary of his grandmother. When he finally went off to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1890 to study mathematics, she assumed it was a temporary diversion. After all, he was a Russell, and great things were expected of him—it would not even be surprising if he were to become Prime Minister like his grandfather. She also assumed that his interest in Alys Pearsall Smyth, daughter of American Quakers who lived near Bertie’s Uncle Rollo, was similarly a passing affair. She was horrified when Bertie announced his engagement to Alys in 1893. In his Autobiography, Bertie described Granny’s—and his extended family’s—disapproval of Alys in this way: “They said she was no lady, a baby-snatcher [Alys was all of five years older than Bertie], a low-class adventuress, a designing female taking advantage of my inexperience, a person incapable of all finer feelings, a woman whose vulgarity would perpetually put me to shame.”

Had Granny let things be, Bertie might very well have lost interest in Alys, but it was not in Countess Russell’s nature to do nothing. Her actions to prevent the marriage only heightened Russell’s resolve. One trick she had up her sleeve was to arrange for Bertie to become the honorary attaché of Britain’s ambassador to France, Lord Dufferin, who was a family friend. Bertie agreed on the condition that at the end of the three-month appointment, he would be free to marry Alys. This was amenable to Granny—she believed that the diversions of Paris would soon make him forget his fiancée.

It was while Bertie was serving as attaché that he received this letter, dated 13 September 1894, from Granny. To set the context: she had earlier advised Bertie that the chief secretary for Ireland, Lord Morley, had offered to take on Bertie as his private secretary after his appointment in Paris expired. Bertie had refused and told his grandmother that he was interested in possibly studying economics, and wanted to apply for a fellowship to Trinity. Granny now tells her grandson: “I think it is a great pity you should refuse Morley’s offer—of course I told him of your projected marriage, and he answers that it is not an obstacle.” Granny was still likely believing, or hoping, that the marriage would never come to pass. She continues with a pitch to his family destiny: “I quite sympathize with your desire to study economics, and I also see the advantages of a fellowship—but I cannot but strongly feel that for you, such employment as J.M. offers … would be better than either. … I know your grandfather and your father would have felt as I do in this matter.” She concludes by stating: “I am ambitious for you, my dearest Boy….”

Bertie did not heed Granny’s advice. He returned to England as planned, and he and Alys were married on 13 December 1894. While Bertie’s brother, Frank, attended the ceremony, neither Granny nor any of the other Russells were present. Granny died in 1898 and therefore did not live long enough to say ‘I told you so’ when Bertie and Alys’ marriage virtually ended four years later. (They did not separate until 1911 when Bertie fell in love with Ottoline Morrell; they divorced in 1921 when he married Dora Black). In his Autobiography, Russell noted his reaction to Granny’s death: “I did not mind at all.” But he continued: “in retrospect, as I have grown older, I have realised more and more the importance she had in moulding my outlook on life. Her fearlessness, her public spirit, her contempt for convention, and her indifference to the opinion of the majority have always seemed good to me and have impressed themselves upon me as worthy of imitation.”

Bertrand Russell’s ancestral archives, commonly referred to as the Amberley Papers, form part of the Bertrand Russell Archives.

Sources: (1) Bertrand Russell. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 1872-1914 (Volume I). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd., 1967. (2) Ronald W. Clark. The Life of Bertrand Russell. Jonathan Cape and Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1975; includes Aunt Agatha’s account of Bertie bowing to Queen Victoria. (3) Russell’s ‘Greek Exercises’ book can be seen in the Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 3.34, Document 220.010010.

Rollo’s only doubt as to as to y[ou]r acceptance is

I think whether J.M. w[oul]d agree to a married man

& whether he c[oul]d wait. Good accts. still from Auntie

except that Lillie was shut up with a cold.[1]

Pembroke Lodge,

Richmond,

Surrey

Sep. 13 / 94

Dearest Bertie

I was grow[in]g impatient for a letter – but thought perhaps you were wait[in]g till you c[oul]d tell me someth[in]g of y[ou]r new life & new comrades – I rejoice that all is pleasant, & hope you will be as happy as I found it perfectly easy to be ‘under the circumstances’ – you’ll say that’s too long ago for me to remember, but it’s not! Who is the other honorary attaché? The Baronne[2] gave me particulars about the people to whom you have the letters – some political, some scientific, some charmingly musical -- & all

[second page]

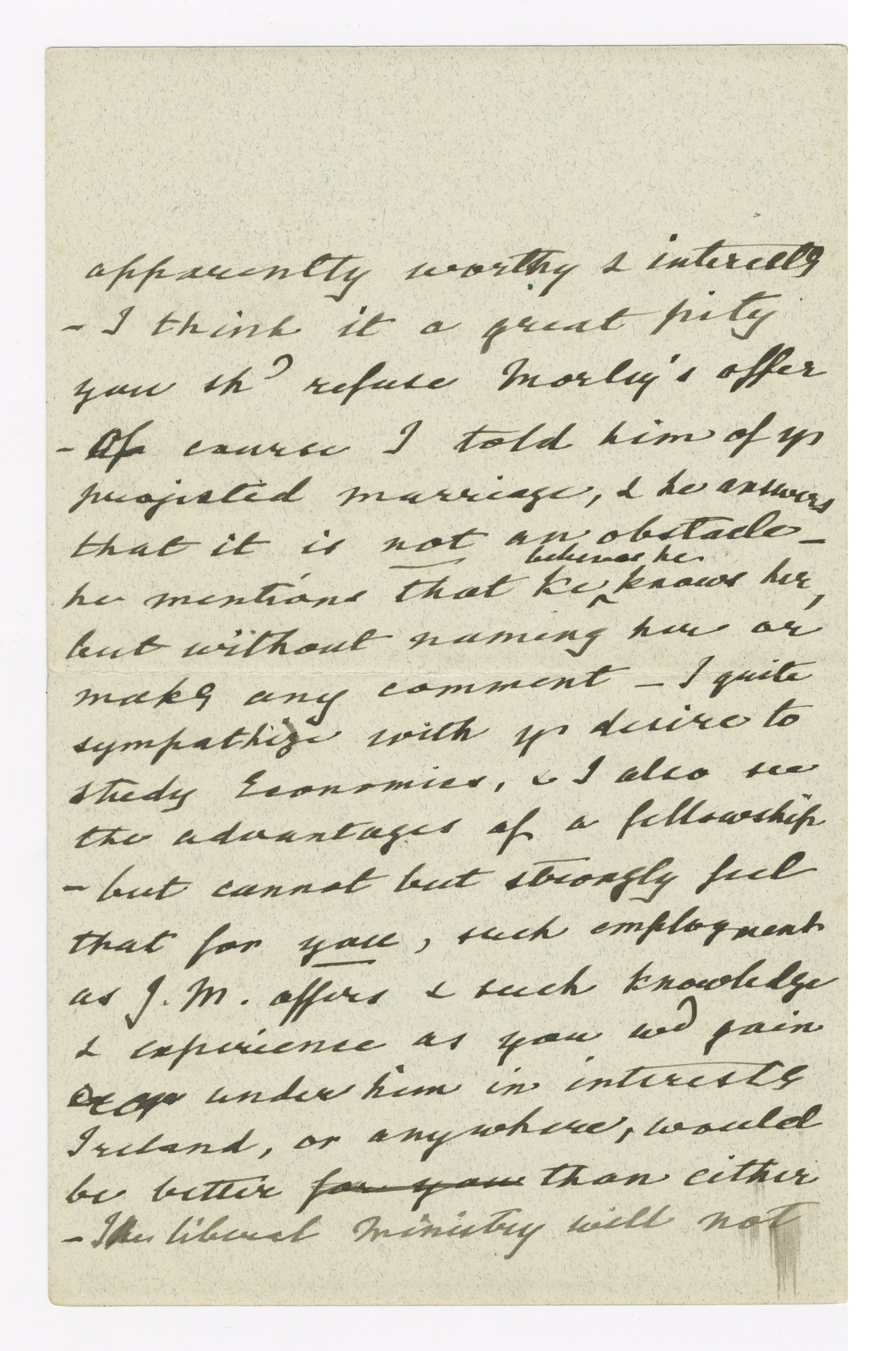

apparently worthy & interest[in]g – I think it is a great pity you sh[oul]d refuse Morley’s offer[3] -- of course I told him of y[ou]r projected marriage, & he answers that it is not an obstacle – he mentions that he believes he knows her, but without naming her or mak[in]g any comment -- I quite sympathize with y[ou]r desire to study economics, & I also see the advantages of a fellowship -- but I cannot but strongly feel that for you, such employment as J.M. offers & such knowledge & experience as you w[oul]d gain under him in interest[in]g Ireland, or anywhere, would be better than either. The liberal Ministry will not

[third page]

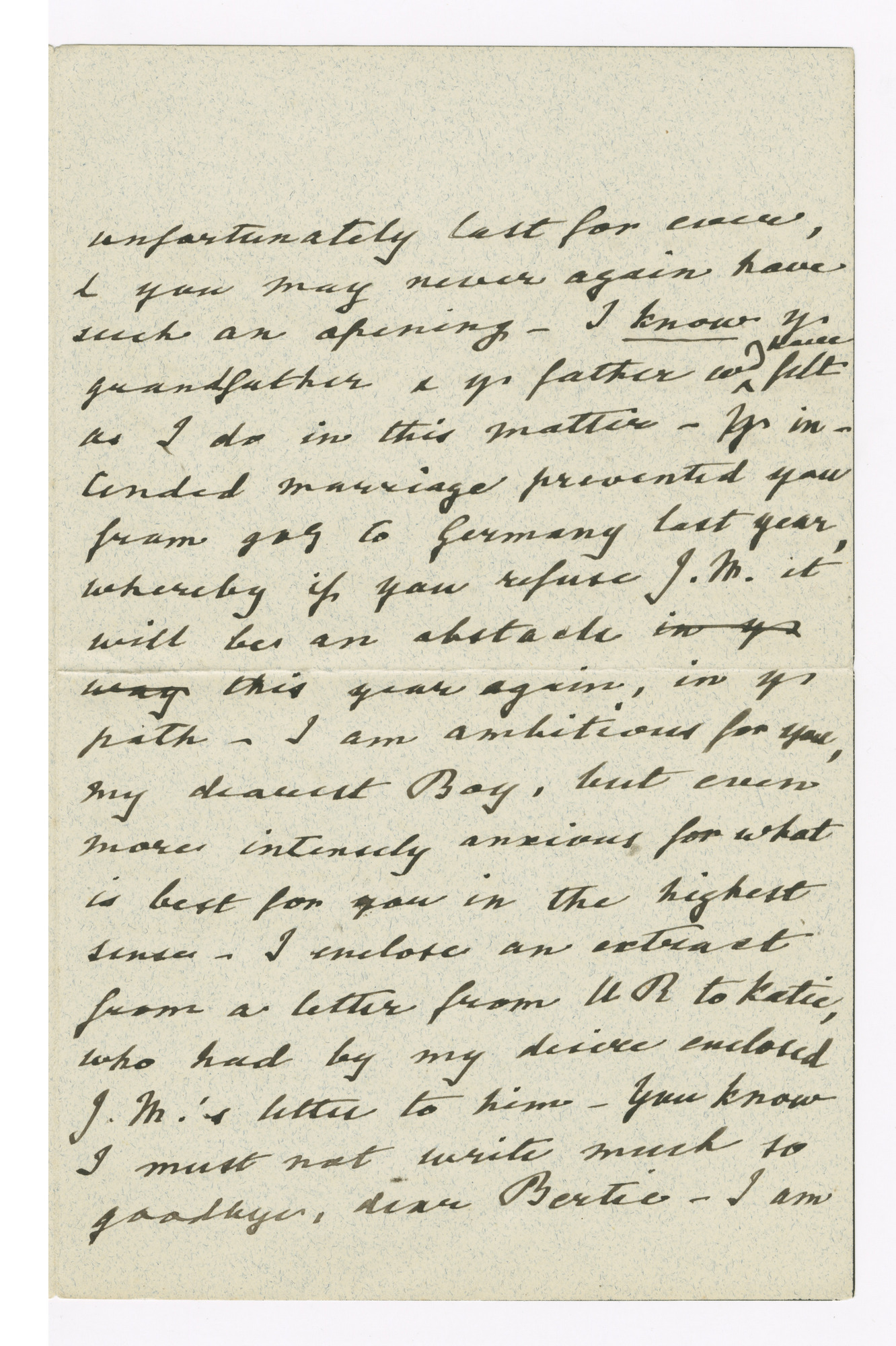

unfortunately last for ever, & you may never again have such an opening. I know y[ou]r grandfather and y[ou]r father w[oul]d have felt as I do in this matter. Y[ou]r intended marriage prevented you from going to Germany last year, whereby if you refuse J.M. it will be an obstacle this year again, in y[ou]r path. I am ambitious for you, my dearest Boy, but even more intensely anxious for what is best for you in the highest sense. I enclose an extract from a letter from UR[4] to Katie, who had by my desire enclosed J.M.’s letter to him – You know I must not write much so goodbye, dear Bertie – I am

[fourth page]

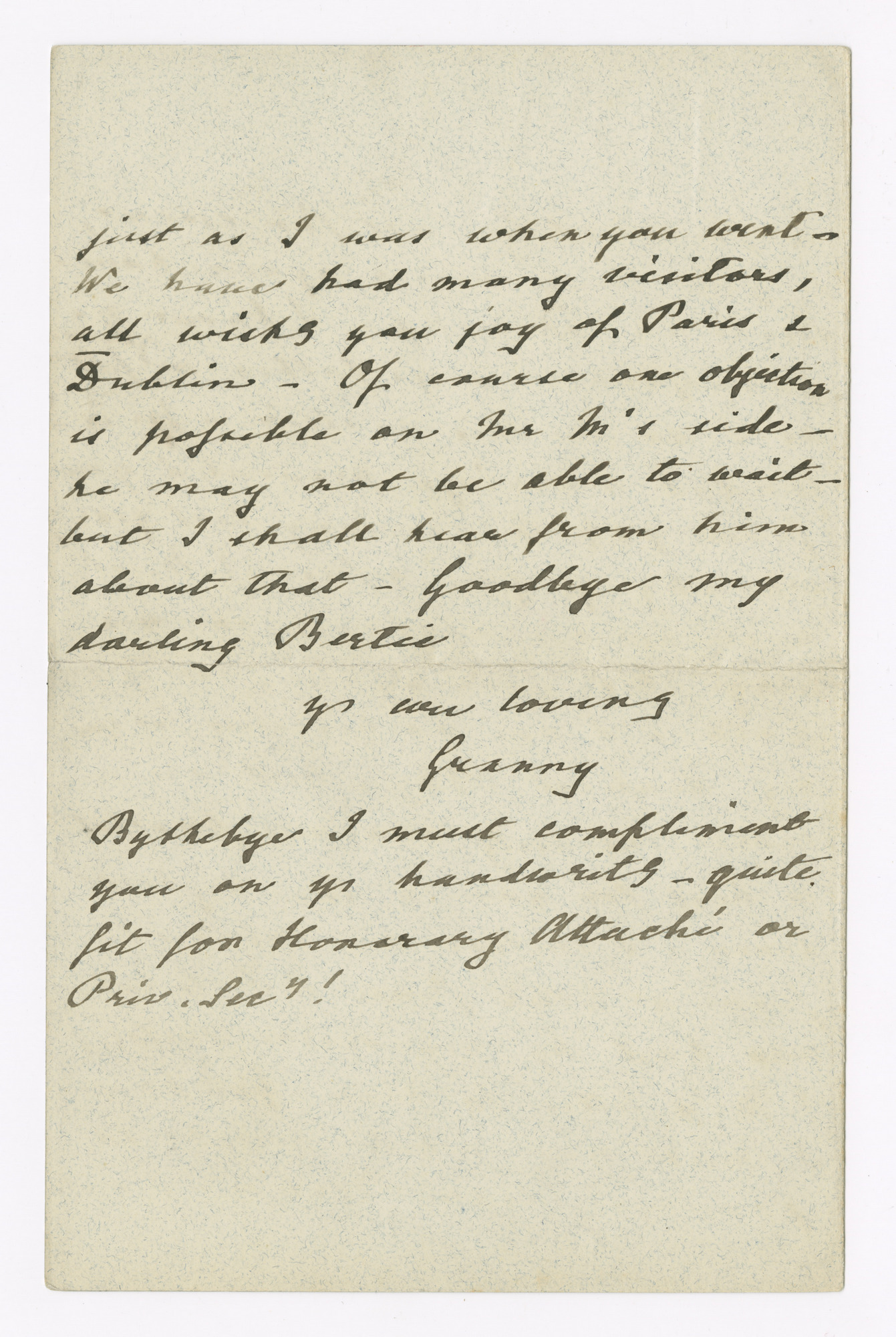

just as I was when you went. We have had many visitors, all wish[in]g you joy of Paris & Dublin. Of course one objection is possible on Mr. M.’s side – he may not be able to wait but I shall hear from him about that. Goodbye my darling Bertie

y[ou]r ever loving

Granny

By the bye I must compliment you on y[ou]r handwriting – quite fit for Honorary Attaché or Priv[ate] Sec[retar]y!

[1] This passage is a postscript to the letter and therefore should be read at the end. See footnote 4.

[2] ‘Baronne’ refers to Lord Dufferin, Britain’s ambassador to France.

[3] Lord John Morley (also ‘J.M.’ in Granny’s letter) was Britain’s chief secretary for Ireland. He was in need of a private secretary and offered the position to Russell.

[4] Russell’s Uncle Rollo. The ‘extract’ is the postscript that appears at the top of the page.

Bertrand Russell Archives, Box 6.30, Document 081112. Public domain.